This is Part III of a multi-part series. Below are the links to other parts of this tutorial!

- Unit Testing Tutorial Part I: Introduction to PHPUnit

- Unit Testing Tutorial Part II: Assertions, Writing a Useful Test and @dataProvider

- Unit Testing Tutorial Part III: Testing Protected/Private Methods, Coverage Reports and CRAP

- Unit Testing Tutorial Part IV: Mock Objects, Stub Methods and Dependency Injection

- Unit Testing Tutorial Part V: Mock Methods and Overriding Constructors

A common question I keep hearing repeated is, “How much do I test?”.

A common response is, “Until you have 100% code coverage.”.

In this third part of my unit testing tutorial, I will explain what code coverage is and why 100% of it may not be what you should aim for.

But first, how to test your private/protected methods!

PROTECTED/PRIVATE METHOD TESTING

If you look at the second part of this series, you will notice that we instantiate our class to be tested via a regular new call. You may also be left wondering how to test protected or private methods if you are unable to access them directly via the instantiated object ( $url->someProtectedMethod() ).

Usually the answer would be, “You do not test protected/private methods directly.”. Since anything non-public is only accessible within the scope of the class, we assume that your class’s public methods (its API) will interact with them, so in the end you are actually indirectly testing these methods anyway.

Of course, there are always exceptions to the rule: What if you are testing an abstract class that defines a protected methods but does not actually interact with it?

What if you want to test different scenarios for a particular method and do not have the opportunity to go through your public methods?

I will explain the process!

Stupid user class

Create a new file at ./phpUnitTutorial/User.php and paste the following:

Let me be very clear: the

Userclass is not a good class. Usingmd5()for passwords should be avoided at all costs! In fact, it is a pretty bad class overall. That said, it provides a very simple and easy to grasp example of what I am teaching.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

<?php

namespace phpUnitTutorial;

class User

{

const MIN_PASS_LENGTH = 4;

private $user = array();

public function __construct(array $user)

{

$this->user = $user;

}

public function getUser()

{

return $this->user;

}

public function setPassword($password)

{

if (strlen($password) < self::MIN_PASS_LENGTH) {

return false;

}

$this->user['password'] = $this->cryptPassword($password);

return true;

}

private function cryptPassword($password)

{

return md5($password);

}

}

Our test would instantiate the User class using $user = new User($details);.

You can access the ::setPassword() method, but are unable to call ::cryptPassword() - but in this case, you do not have to! The fact that your public method interacts with the private method is enough to say, “This method is tested.”, at least with this particular code!

So, how would you create your test for this method? You can see the constructor and ::setPassword() methods both require a parameter. PHPUnit requires no special magic to work with method parameters, as you will soon see.

Creating your test

Create your empty test at ./phpUnitTutorial/Test/UserTest.php and setup the skeleton:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

<?php

namespace phpUnitTutorial\Test;

class UserTest extends \PHPUnit_Framework_TestCase

{

//

}

Running your test suite will result in an error:

1

2

1) Warning

No tests found in class "phpUnitTutorial\Test\UserTest".

This is great because it tells us PHPUnit has picked up this test and it is ready for actual code!

We should identify what we would like to test before we go any further. As the phpUnitTutorial\User class is very simple, we can quickly see two scenarios:

::setPassword()returnstruewhen password is set, and::getUser()returns the user array, which would contain the new password which we would then compare against expected result.

We will start with ::setPassword() returning true. Create the empty method:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

<?php

// ...

public function testSetPasswordReturnsTrueWhenPasswordSuccessfullySet()

{

//

}

The phpUnitTutorial\User constructor is expecting a parameter, so define it before instantiating the object:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

<?php

namespace phpUnitTutorial\Test;

use phpUnitTutorial\User;

class UserTest extends \PHPUnit_Framework_TestCase

{

public function testSetPasswordReturnsTrueWhenPasswordSuccessfullySet()

{

$details = array();

$user = new User($details);

}

}

Note I have added a use statement.

We will now define the parameter required for the ::setPassword() method, and then call it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

<?php

// ...

public function testSetPasswordReturnsTrueWhenPasswordSuccessfullySet()

{

$details = array();

$user = new User($details);

$password = 'fubar';

$result = $user->setPassword($password);

}

We expect $result to equal true, and I know just the assertion to use, assertTrue()! Here is our completed test:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

<?php

// ...

public function testSetPasswordReturnsTrueWhenPasswordSuccessfullySet()

{

$details = array();

$user = new User($details);

$password = 'fubar';

$result = $user->setPassword($password);

$this->assertTrue($result);

}

If you run your test suite, you will get a nice green bar for your troubles.

We can now focus on testing ::getUser(), which is a one-line method so it should be very simple to test, right? Well… not exactly. You see, the whole reason to even test ::getUser() is to give us access to the private, and therefor inaccessible $user property. We want to verify that the $user property has values that we expect - like passwords structured in the correct way.

What this means is that by testing ::getUser() we are also going to end up testing ::__construct(), ::setPassword() and ::cryptPassword().

Here is our empty test:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

<?php

// ...

public function testGetUserReturnsUserWithExpectedValues()

{

//

}

The only thing we can really test in our particular scenario is that the password that was created by ::cryptPassword() matches our expectations. First, set up the method similar to how we did with ::testSetPasswordReturnsTrueWhenPasswordSuccessfullySet():

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

<?php

// ...

public function testGetUserReturnsUserWithExpectedValues()

{

$details = array();

$user = new User($details);

$password = 'fubar';

$user->setPassword($password);

}

We do not catch the result of ::setPassword() because we are going to assume it passed. If it did not pass, we will know for sure in the next steps.

We know our raw password is fubar. We can see that this password is “hashed” in ::setPassword() using md5(). Therefor we can define what we expect our result to actually be:

$expectedPasswordResult = '5185e8b8fd8a71fc80545e144f91faf2';

We then call ::getUser() to get the user in its current state:

$currentUser = $user->getUser();

What are we expecting our test to actually do?

We are expecting ::getUser() to return an array, and we want to compare the password key to our expected value. The perfect assertion for this would be assertEquals(). Here is our completed test:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

<?php

// ...

public function testGetUserReturnsUserWithExpectedValues()

{

$details = array();

$user = new User($details);

$password = 'fubar';

$user->setPassword($password);

$expectedPasswordResult = '5185e8b8fd8a71fc80545e144f91faf2';

$currentUser = $user->getUser();

$this->assertEquals($expectedPasswordResult, $currentUser['password']);

}

PHPUnit seems to have liked our test:

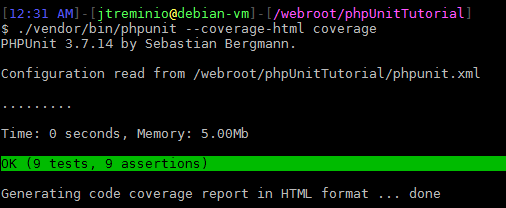

OK (9 tests, 9 assertions)

Targeting private/protected methods directly

What if we simply want to write more scenarios for a protected method? What if we do not want to go through the public API directly, and instead want to interact solely with the protected method?

There are scenarios where this would be a legitimate need. I will not go through those possible scenarios today (I will in an upcoming part of my series!), but suffice it to say that with a little creative thinking, you can access your instantiated objects’ privates rather easily:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

<?php

// ...

/**

* Call protected/private method of a class.

*

* @param object &$object Instantiated object that we will run method on.

* @param string $methodName Method name to call

* @param array $parameters Array of parameters to pass into method.

*

* @return mixed Method return.

*/

public function invokeMethod(&$object, $methodName, array $parameters = array())

{

$reflection = new \ReflectionClass(get_class($object));

$method = $reflection->getMethod($methodName);

$method->setAccessible(true);

return $method->invokeArgs($object, $parameters);

}

Using invokeMethod() you can easily call your private or protected methods directly without having to go through public methods.

To use, you simply do

1

2

3

4

<?php

// ...

$this->invokeMethod($user, 'cryptPassword', array('passwordToCrypt'));

This would be the equivalent of simply typing

1

2

3

4

<?php

// ...

$user->cryptPassword('passwordToCrypt');

assuming ::cryptPassword() were public.

COVERAGE REPORT

Imagine you have a large codebase, as well as several hundred unit tests. You are confident that most of your code is well-tested, but you need to make sure.

You could go through each test and manually verify that every bit of your codebase is covered, but that sounds boring, and like a lot of work. Programmers love being lazy, and thankfully there is a very powerful tool that ships with PHPUnit that allows us to continue being lazy!

The coverage report tool generates static HTML files for you to browse through and immediately see statistics of your codebase, including how much is covered by tests and how complicated your code is.

It will even tell you if you have missed any possible routes through our tested code, like not triggering an if statement and running the code inside the block, for example.

Generating a coverage report

To generate, simply pass the --coverage-html flag to PHPUnit, along with the destination to have the files generated. I usually use a folder coverage:

1

./vendor/bin/phpunit --coverage-html coverage

|

|---|

| 01-coverage-report.png |

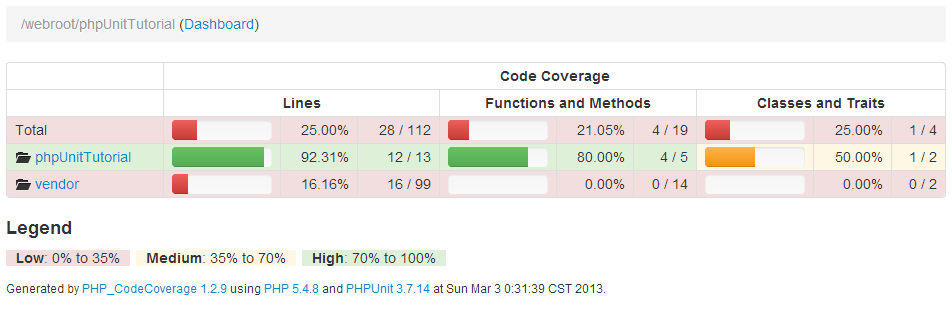

If you look at your filesystem now, you will see that a coverage folder has been created and filled with HTML files. Open the index.html file and you will see:

|

|---|

| 02-coverage-report-dashboard.png |

[message info]If you are using an older PHPUnit version, it may look slightly different as the CSS was changed in a recent update![/message]

Ignore the vendor folder, focus instead on your own code. Click into phpUnitTutorial and you will see two entries for the two files you currently have.

Wait, only 2?

That is right, astute reader! You actually have 3 test files, and one of them is not listed on this page: StupidTest.php. That is because this test does not actually correspond to any code within our codebase, so PHPUnit did not generate a coverage report for it.

URL test coverage

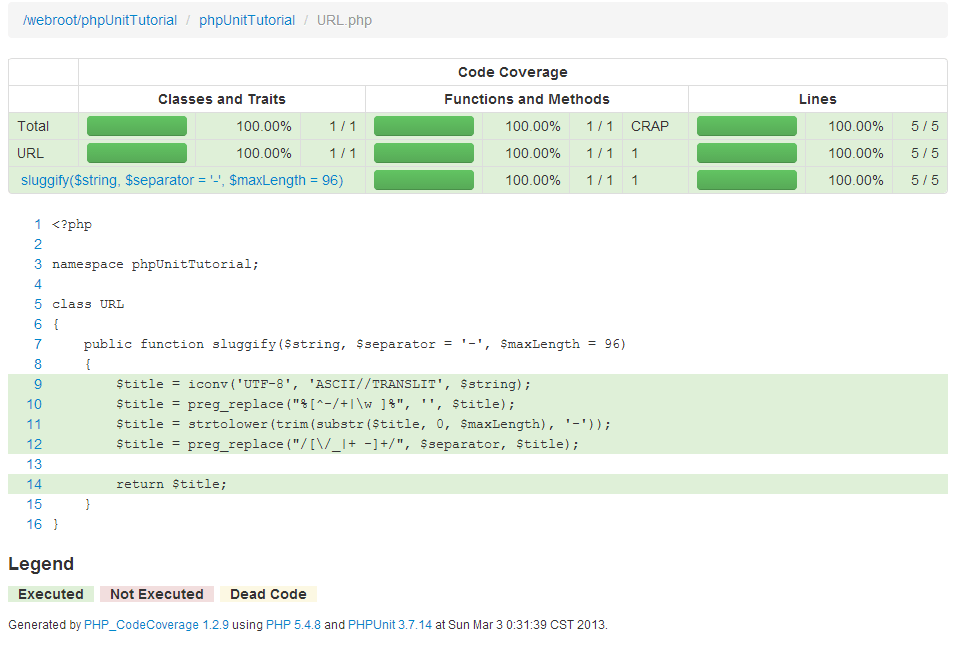

Click into URL.php in the coverage report, and you will see:

|

|---|

| 03-url.php-coverage-report.png |

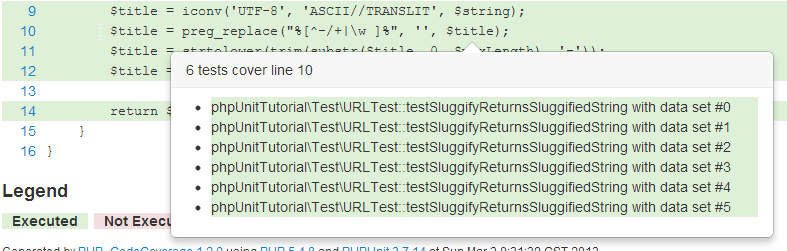

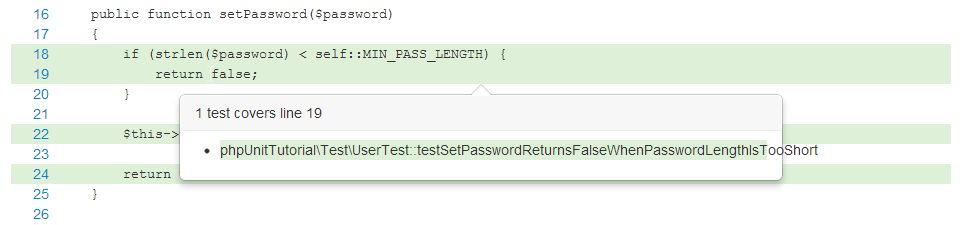

Looking at the legend at the bottom of the page tells you that green is executed code, red is not executed, and yellow is dead code. In this particular example, all the lines with code are green. If you hover over one of the lines, a small info box will popup and show you which tests cover this particular line:

|

|---|

| 04-line-covered-by.png |

This code is really straightforward, so it may not have the impact to make you go, “Cool!”, but it gives you a taste of what is to come.

User test coverage

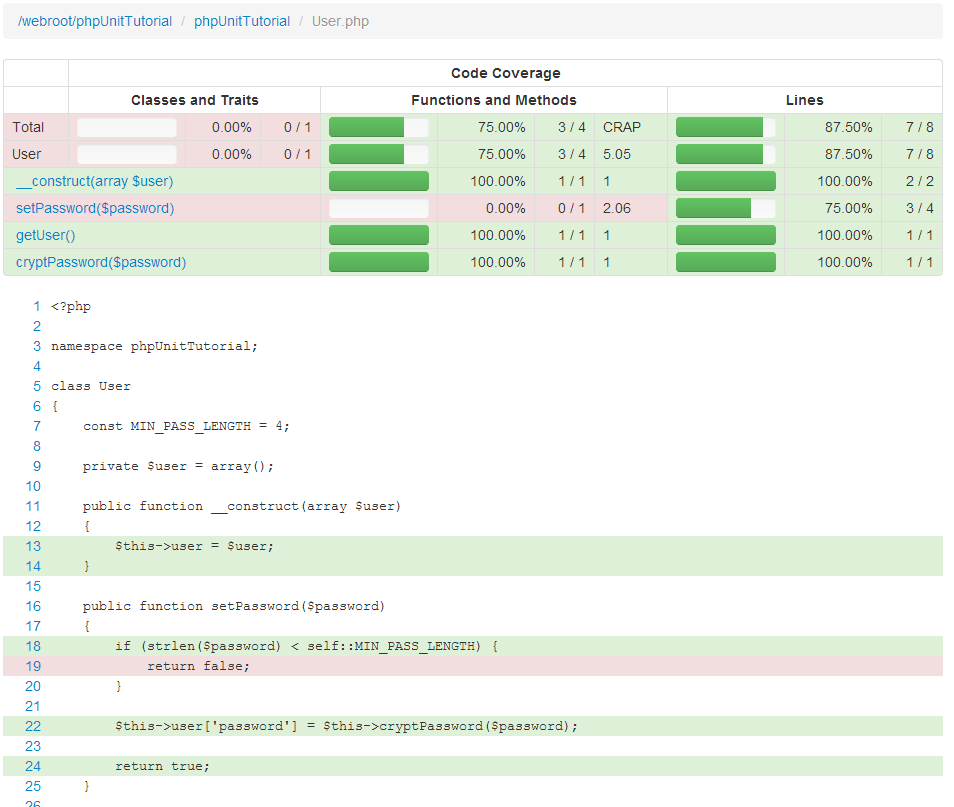

Go back a page and click into User.php:

|

|---|

| 05-uncovered-line.png |

Looking at this report, you can immediately tell that something is red.

Specifically, the if statement inside ::setPassword() never resolves to true in any of our tests, so the code inside of it is never run.

For this particular if statement, the contents are extremely simple: it returns false.

Go back to phpUnitTutorial\Test\UserTest and create a new method to test this scenario:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

<?php

// ...

public function testSetPasswordReturnsFalseWhenPasswordLengthIsTooShort()

{

//

}

In a previous test, ::testSetPasswordReturnsTrueWhenPasswordSuccessfullySet(), the password we passed in to ::setPassword() was 5 characters in length. To trigger the if block, we need to pass in a password that is less than 4 characters in length. The rest is pretty much the same as before:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

<?php

// ...

public function testSetPasswordReturnsFalseWhenPasswordLengthIsTooShort()

{

$details = array();

$user = new User($details);

$password = 'fub';

$result = $user->setPassword($password);

}

We are expecting $result to be false. There is an assertion for that! assertFalse() returns true if the value you pass it is false. Here is our completed test:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

<?php

// ...

public function testSetPasswordReturnsFalseWhenPasswordLengthIsTooShort()

{

$details = array();

$user = new User($details);

$password = 'fub';

$result = $user->setPassword($password);

$this->assertFalse($result);

}

Run your test suite and you get OK (10 tests, 10 assertions).

Re-run your coverage report, reload the page, and you should now see that red line has turned to green. If you hover over it, it will tell you this new test now covers it.

|

|---|

| 06-user.php-coverage-report.png |

PAY ATTENTION TO YOUR CRAP

If you look at the top of your coverage reports, you will see a column labeled “CRAP”.

Officially it stands for “Change Risk Analysis and Predictions”, but I like to think of it as how hard it will be to come back to a particular method in the future and figure out what exactly is going on.

A thorough description of the CRAP index can be found here.

I would not blame you for quickly closing that link. It is a bit dry, maybe a little boring if you are not really interested in the intricacies of what the CRAP index is.

Suffice it to say, the higher your method’s CRAP index, the harder it is to understand.

If your code is extremely simple - is little more than a getter, then its CRAP index is close to 1 (1 being the lowest value possible). If your code is a little more complex, say with a few if blocks, your CRAP value starts creeping up.

If you throw a few foreach and nested statements, your CRAP will shoot right up!

As you write tests to cover the different execution pathways your CRAP index will start climbing down. Once the method is fully covered, the final number will usually be much lower than the number shown when no tests cover it.

So far our code has been fairly simple and to the point. There are not very many different pathways of execution, keeping our CRAP fairly low. This is the way I prefer to code: small, but plentiful methods doing very specific tasks. Not only is this much easier for a human to comprehend, but it allows more versatile refactoring of code while still allowing your tests to continue passing.

100% CODE COVERAGE AND WHY IT IS NOT NEEDED

Many developers espouse the notion of writing unit tests until you have complete, 100% coverage. The arguments sound eerily similar to the tabs vs spaces crowd, so I tried lightly.

I do not believe 100% code coverage is needed: if your method has a CRAP index < 5, it is not complex enough to warrant a test.

That said, a method with a CRAP index < 5 is probably simple enough that a test for it would take less than 5 minutes to write, so the decision of how much time you want to dedicate to writing basic tests is ultimately up to you!

WRAPPING UP

Today you learned that testing private/protected methods can be done either indirectly, or “cheating” using the ReflectionClass class.

You also learned how to use the amazingly useful code coverage generator to track down code that had not been covered, and I possibly convinced you that writing 100% test coverage is unnecessary.

I believe we are finally at the stage that we can introduce more advanced concepts, like mock objects and mock/stub methods, the awesomeness (and necessity) that is dependency injection and/or service container and tracking down unforeseen issues when refactoring code.

All that and more is coming up in my next chapter!

Until next time, this is Señor PHP Developer Juan Treminio wishing you adios!

- Previous →

Unit Testing Tutorial Part II: Assertions, Writing a Useful Test and @dataProvider - ← Next

Unit Testing Tutorial Part IV: Mock Objects, Stub Methods and Dependency Injection